"The question is not what you look at, but what you see."

- Henry David Thoreau

Basic Concepts in Visual Field Loss

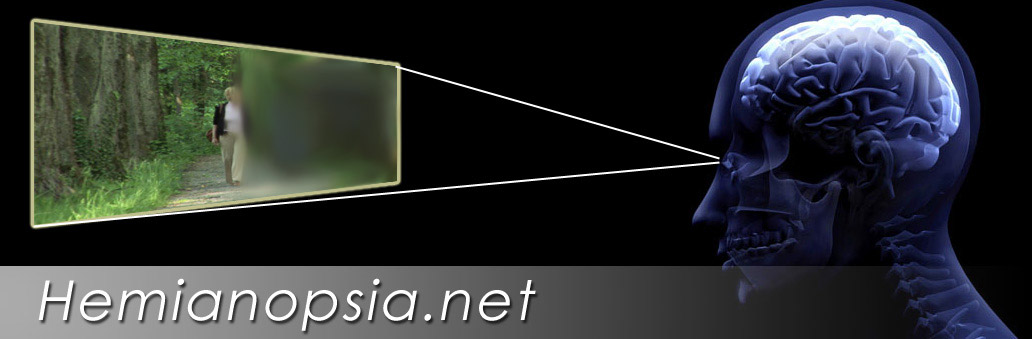

Homonymous Hemianopsia

Homonymous hemianopsia, also referred to as homonymous hemianopia is the loss of half of the field of view on the same side in both eyes. It occurs frequently in stroke, tumor and traumatic brain injuries, because of the manner in which the nasal nerve fibers from each eye cross as they pass to the back of the brain. The visual images that we see to the right side travel from both eyes to the left side of the brain, while the visual images we see to the left side in both eye travel to the right side of the brain. Therefore, damage to the right side of the posterior portion of the brain can cause a loss of the left field of view in both eyes. Likewise, damage to the left posterior brain can cause a loss of the right field of vision.

Homonymous Quadranopsia

One type of incomplete hemianopsia is the quadranopsia. A quadranopsia is related to the location of the lesion in the brain. It involves only one quarter of the visual field. It may be a superior or inferior quadranopsia and occur on the right or left side. There are several locations including the temporal and parietal lobes that lead to quadranopsia but studies suggest that the majority occur in the occipital lobe.

Patients can be taught the compensatory strategy of tilting the head to move the seeing area into position. For example, right superior quadranopsia patients can tilt their head to the left bringing up the remaining inferior side vision to the horizontal. Thus a right inferior quadranopsia patient would tilt the head to the right.

Macular Splitting

The macula is the area of best visual acuity and is the center of our fixation. When we read we turn our eyes to place the image on the macular region. Macular splitting is a hemianopsia that results in a loss of vision with a precise vertical boundary of seeing versus non-seeing though the very center of our central vision. Macular splitting has more negative impact on functioning especially in reading and particularly in a right hemianopsia. A word may fall partly in the seeing and partly in the non-seeing area causing confusion. It may also become difficult to detect the beginning or end of a line of text.

The macula is the area of best visual acuity and is the center of our fixation. When we read we turn our eyes to place the image on the macular region. Macular splitting is a hemianopsia that results in a loss of vision with a precise vertical boundary of seeing versus non-seeing though the very center of our central vision. Macular splitting has more negative impact on functioning especially in reading and particularly in a right hemianopsia. A word may fall partly in the seeing and partly in the non-seeing area causing confusion. It may also become difficult to detect the beginning or end of a line of text.

Macular Sparing

Macular sparing results when a hemianopsia causes a loss of visual field, which leaves a small area of functioning vision on the side of the loss at the center of our vision. This may be only a few degrees but may help the patient see full words or detect the start or end of the line in reading. The more sparing that occurs the better the outcome for many patients. Higher amounts of sparing may improve the potential to return to higher functioning such as returning to work or driving in some patients.

Macular sparing results when a hemianopsia causes a loss of visual field, which leaves a small area of functioning vision on the side of the loss at the center of our vision. This may be only a few degrees but may help the patient see full words or detect the start or end of the line in reading. The more sparing that occurs the better the outcome for many patients. Higher amounts of sparing may improve the potential to return to higher functioning such as returning to work or driving in some patients.

Congruent versus Incongruent Hemianopsia

A congruent visual field defect presents with the same exact shape in the field of both eyes. Visual fields that are different in shape are considered incongruent. More incongruent fields may point towards lesion of the optic tracts, while congruent defects point more towards the visual cortex of the occipital lobe.

Complete versus Incomplete Hemianopsia

Complete homonymous hemianopsia means the entire half of the visual field is impaired. Hemianopsias, however, are often incomplete. Depending on the location of the lesion and the type of injury some areas within the loss may be less impaired. Generally, the more incomplete the hemianopsias, the better the potential for rehabilitation. This is because any remaining vision on the side of the loss may help the patient maintain at least a basic sense of spatial detection on that side. Additionally as we observe patients clinically, the new incomplete cases seem to have more potential for early spontaneous improvement than complete hemianopsia cases.

Homonymous Sectoropias of the Lateral Geniculate Body

Lesions of the lateral geniculate body (LGB) are rare. Massive damage to the LGB can cause an incongruent homonymous, but the unique visual field losses from the lateral geniculate body relates to the dual circulation to the region. Each blood supply supports a different portion of the lateral geniculate body. Thus unique visual field lesions may occur based on which vascular supply is affected. The central fixation is usually involved due to the anatomy of the LGB, but pupil reflexes are usually spared since the pupillary fibers leave the optic tracks before reaching the LGB.

The Midline Homonymous Sectoropia: In lateral choroidal ischemia (posterior cerebral) of the LGB, a sectorial defect may extend like a wedge straddling the horizontal midline pointing towards the macular region.

The Upper/Lower Homonymous Sectoropias : If the anterior choroidal artery (internal carotid circulation) is affected to the LGB, a wedge like area may retain function, but the areas above and below that area on the side of the field loss may be lost.

Hemianoptic Scotomas of the Occipital Lobe

Unlike hemianopsias, homonymous hemianoptic scotomas (blindspots) are smaller areas of vision loss surrounded by and area of vision. These are found in the vision opposite the lesion.

Macular Homonymous Hemianoptic Scotomas: Small posterior lesions in the occipital lobe in one hemisphere may create a small homonymous hemianoptic scotoma (blindspot) on the opposite side. The patient may not understand the loss but have difficulty in reading, especially if the visual field loss is on the right side. The defect will be missed upon confrontations, but may be detected on threshold visual field testing and by manually plotting the loss with a small white target on an Amlser Grid chart.

Peripheral Hemianoptic Scotomas: Small posterior lesions may also produce homonymous hemianoptic scotomas which are sharply defined and congruent blindspots in the peripheral visual field.

Temporal Crescent Lesions of the Occipital Lobe

Unilateral Temporal Crescent Scotoma or Half Moon Syndrome: An anterior lesion on one side of the occipital lobe can produce a unilateral crescent shaped loss on the far periphery of the opposite eye. This occurs out 60 degrees from the center fixation. These are not homonymous because the nasal fibers that carry the signal do not cross to different sides of the brain. This is the opposite of a retained Temporal crescent.

A Retained Temporal Crescent: Hemianopsia that occur in a specific location in the occipital lobe may result in a hemianopsia in which at the far temporal side of the hemianopsia, a crescent shape area of vision is retained. This usually is about 60 degrees out from straight ahead and extended to the 90 degrees from straight ahead.

This can help the patient in mobility especially in being less startled since objects moving in front of the patient from that side are initially detected as they pass through the retained area. Unfortunately the actual visual field loss in defect in these patients may be missed if careless confrontations are done only at the far periphery on both sides.

Above Photos: This patient presented with a left temporal crescent. In the first picture he demonstrates his ability to see his hand to the far side. In the second (right) picture, he shows where his hand starts to disappear.

Picture Below. Note that the 30-2 Humphrey Field did not pick up the temporal crescent. This points to the importance of careful confrontation field testing combined with computer testing.

Unusual Visual Fields from Bilateral Occipital Lobe Lesion

Checkerboard Visual Field Defect: Bilateral quadranopsia caused by two separate lesions one above the calcarine fissure on one side of the brain and one below on the opposite side can produce a checkerboard pattern. This can occur from two simultaneous events or events separated in time.

Altitudinal Hemianopsia from the Occiptal Lobe: Most altitudinal hemianopsia are seen clinically from lesions of the optic nerves from conditions such as ischemic optic neuropathy. However, bilateral lesions on the opposite sides of the occipital lobe, with either both above or both below the calcarine fissure can produce two quadranopsia that together create an attitudinal hemianopsia.

The visual field defect above can be created by bilateral anterior ischemic optic neuropathies affecting both optic nerves. It can also be caused by bilateral inferior quadranopsias from superior lesions on both sides of the occipital lobe.

Bilateral Homonymous Hemianopsia: A large lesion that effects both sides of the occipital lobe can create a bilateral homonymous hemianopsia which is a loss of both sides of the visual field in both eyes and cortical blindness. Visual acuity may be significantly impaired.

Bilateral Homonymous Hemianoptic Scotomas: One central blindspot in the middle of fixation can occur from the combination of two small lesions of the occipital lobe resulting in bilateral hemianoptic scotomas.

Peripheral Ring Scotomas: Bilateral occipital lobe lesion in the mid zone of the visual cortex may create a ring scotoma.

Blindsight (Riddoch Phenomenon)

Blindsight refers to an ability to detect shape, color, or motion in the area of an otherwise complete hemianopsia. Blind sight was first reported after World War I by George Riddoch, a British military physician. Riddoch observed that some of his patients with hemianopsias could see motion in an otherwise totally impaired visual field. His reports were quickly criticized by neuro-scientists, but decades later he was proven correct.

Because processing of vision is divided into different discrete segments in the brain to perceive color, motion and form, it is possible to damage some areas and spare others. Patients with Blindsight do not consciously see in their lost visual field in the manner we all experience vision, but on forced-choiced tests demonstrate they can detect forms, colors or motion. These patients do not report it as vision, but rather as a non-visual sensation or “feeling” of a shape or color or motion.

Please contact us if you have any questions.

The Low Vision Centers of Indiana

Richard L. Windsor, O.D., F.A.A.O., D.P.N.A.P.

Craig Allen Ford, O.D., F.A.A.O.

Laura K. Windsor, O.D., F.A.A.O.

Indianapolis (317) 844-0919

Fort Wayne (260) 432-0575

Hartford City (765) 348-2020