"In the depth of winter I finally learned that within

me there lay an invincible summer."

- Albert Camus

Driving After Stroke or Brain Injury

Driving is often a concern for the patient recovering from a head injury or stroke. Every patient suffering brain injury from stroke or other trauma, regardless of a known visual field loss should have a complete eye examination with visual fields testing. No patient should return to driving without an eye examination.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) patients do not always appreciate their new deficits and may assume their driving skills are adequate when significant safety risks may still be present. The decision whether a patient may safely return to driving should be a team effort. The professionals dealing with each patient’s driving issues will vary but the following are some of the professionals who may be involved in the driving decision; certified driving rehabilitation specialists, the family physician, neurologist, physiatrist, neuro-psychologist, occupational therapists, physical therapist, optometrist, optometric low vision/neuro rehabilitative specialist and ophthalmologist and/or neuro-ophthalmologist. The patient and family members should also be involved.

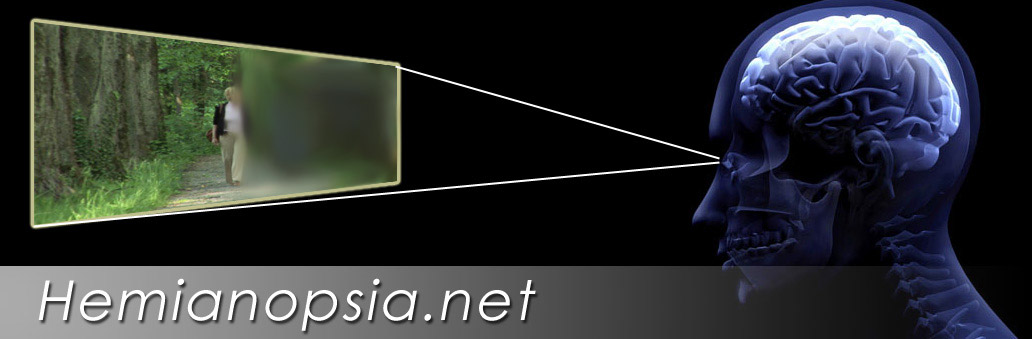

Driving with Homonymous Hemianopsia

Several separate sets of issues determine whether patients with a homonymous hemianopsia may return to driving. First, and foremost, does the patient have the physical stamina, reaction time, attention, discipline, emotional stability, cognitive and perceptual skills to learn to compensate for the visual field loss? Patients with hemi-spatial in-attention (visual neglect) lack the ability to attend to the area of loss and thus are not candidates to drive. An active seizure disorder history may eliminate consideration as well.

Patients with significant multiple deficits in combination with hemianopsia may not be good candidates, but each should be looked at individually. Referral for outside medical and neuropsychological consultations regarding these physical issues may be indicated.

Second, state laws vary in requirements for visual field. Some states have set minimum visual field sizes that cannot be met by a driver with a homonymous hemianopsia. In our years of working with homonymous hemianopsia patients, we have found many patients who had returned to driving on their own by only passing a BMV visual acuity test without proper evaluation and training and without optical systems or extra mirrors that could aid them. Some state may not allow a patient to return to driving despite the patient’s ability to return to safe driving. Hopefully as more studies define the ability of hemianoptic drivers to drive safely, laws in this states may be modified.

Third, will the patient benefit from and accept the use of the adaptive devices and training necessary to reach a safe level of driving? Some patients may lack the stamina, emotional stability or discipline to accept the necessary adaptive aids and training.

Steps to Driving with Hemianopsia

We first test and eliminate those who are poor candidates. Only a small number of all homonymous hemianopsia patients will be candidates for returning to drive. Candidates must demonstrate no hemispatial inattention, no major physical or cognitive barriers as discussed above. Patients with strokes isolated to the occipital lobe only are often good candidates, as they do not show paresis, hemispatial neglect, impaired saccades or perceptual deficits. Additional neuropsychological or medical consultations may be considered in some patients.

We first test and eliminate those who are poor candidates. Only a small number of all homonymous hemianopsia patients will be candidates for returning to drive. Candidates must demonstrate no hemispatial inattention, no major physical or cognitive barriers as discussed above. Patients with strokes isolated to the occipital lobe only are often good candidates, as they do not show paresis, hemispatial neglect, impaired saccades or perceptual deficits. Additional neuropsychological or medical consultations may be considered in some patients.

Next, patients are usually fit with a visual field awareness system such as the EP Horizontal Lens, Chadwick Hemianopsia Lens or the Gottlieb VFAS on the side of the loss. The EP Horizontal Lens presents a continuous view and may offer some additional benefits in driving.These lenses are used to fill in the far peripheral vision on the side of the loss. They also help in city driving to aid in pedestrian detection. These systems are used in combination with head and eye movements to expand the visual field.

An exception to prescribing a visual field awareness system may be patients with exotropias (an eye turning out) with anomalous correspondence. These patients have a natural expanded visual field from the eye drifting out and thus may not require further optical field expansion.

We avoid the use of press-on prisms in driving candidates due to the loss of contrast compared to the much better optical quality of systems like the Gottlieb, EP Horizontal and Chadwick Hemianopsia Lens.

Next, the patient undergoes extensive training in scanning with the low vision specialist and/or occupational therapist. One excellent therapy is descriptive driving,  where the patient sits as a passenger and reports everything seen on both sides. The driver challenges the patient and provides feedback if something is missed. This therapy is used to improve scanning even when driving is not a goal. Another excellent therapy is table tennis. The back and forth and side to side action helps teach scanning and the proprioceptive feedback from the legs and torso is beneficial. Both of these therapies have the common theme that they occur in real time forcing the patient to demonstrate adequate reaction time. An order for occupational therapy is often indicated. We work with many outside occupational therapists. Some area occupational therapists can use a Dynavision system to further develop quick accurate scanning. After saccadic eye movements to scan into the visual field loss have been improved, the patient will require a behind-the-wheel evaluation and training.

where the patient sits as a passenger and reports everything seen on both sides. The driver challenges the patient and provides feedback if something is missed. This therapy is used to improve scanning even when driving is not a goal. Another excellent therapy is table tennis. The back and forth and side to side action helps teach scanning and the proprioceptive feedback from the legs and torso is beneficial. Both of these therapies have the common theme that they occur in real time forcing the patient to demonstrate adequate reaction time. An order for occupational therapy is often indicated. We work with many outside occupational therapists. Some area occupational therapists can use a Dynavision system to further develop quick accurate scanning. After saccadic eye movements to scan into the visual field loss have been improved, the patient will require a behind-the-wheel evaluation and training.

Next, the patient undergoes a rehabilitation driving evaluation and training with a certified driving rehabilitation specialist including a behind-the-wheel evaluation. If the patient shows potential to drive safely, further behind-the-wheel training is performed. The amount of training is individually determined in each case. Upon the completion of training, the patient may be required to pass a BMV courtesy behind-the-wheel driving test.

Additional mirrors may be added to further fill the visual field. We place a wide  panoramic mirror over the rear view mirror. This allows the mirror to be aims slightly in the direction of the loss. It is wide enough to provide the rear view while providing better view to the side. Then we add a small mirror to the windshield just to the side of the steering wheel opposite the field of loss. It is angled to show the front window and the side of the loss. This is used to catch movement in the window while looking ahead.

panoramic mirror over the rear view mirror. This allows the mirror to be aims slightly in the direction of the loss. It is wide enough to provide the rear view while providing better view to the side. Then we add a small mirror to the windshield just to the side of the steering wheel opposite the field of loss. It is angled to show the front window and the side of the loss. This is used to catch movement in the window while looking ahead.

When all of these items come together we have the patient scanning back and forth to scan the field ahead, we have the visual field expander increasing that range and giving constant feedback on the side of the loss. Then we add the mirrors to fill in the remaining areas.

Lane Positioning in Hemianopsia

The loss of the visual field may effect the patient's perception of where "straight ahead" resides. This may result in patients crowding one side of the lane. Behind-the-wheel training should address lane positions in straight roads and particularly on curves. There is usually a bias away from the side of the visual field loss.

A study by researcher at Harvard's Schepens Eye Research Institute found:

"Even with a modest sample size, our results provide evidence that drivers with hemianopia adopted a lane position with a bias away from the blind side. These effects varied individually, with segment type, and were more apparent for right than left hemianopes. However, with the exception of rural right curves, hemianopes did not spend a greater percent time out of lane than the NS drivers on the analyzed straight and curved road segments."

Effects of Hemianopsia on Lateral Position in a Driving Simulator, E Peli, A. R. Bower, A.J.Mandel and R.B. Goldstein, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008.

Example One: An untrained patient with a right homonymous hemianopsia may show a mild bias to shift further left.

Example Two: An untrained patient with a left homonymous hemianopsia may show a mild biases to drive towards the right side.

With behind-the-wheel training most patients learn to compensate. This compensation is crucial if the patient is to return to driving.

Please contact us if you have any questions.

The Low Vision Centers of Indiana

Richard L. Windsor, O.D., F.A.A.O., D.P.N.A.P.

Craig A. Ford, O.D., F.A.A.O.

Laura K. Windsor, O.D., F.A.A.O.

Ali E. Prible, O.D.

Indianapolis (317) 844-0919

Fort Wayne (260) 432-0575

Hartford City (765) 348-2020